What’s Happening in Neuromonitoring? This is a question that gets posed to me all the time from all corners of our profession. CEOs, managers, neuromonitorists, nonphysician doctors, neurologists, attorneys, and even surgeons contact me because they see major changes in intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM), but don’t know what to make of it. The truth is, while many people display public optimism, they all share private concerns. “I’m starting to get worried,” they say. “Where is this thing going?”

So, what IS happening in neuromonitoring?

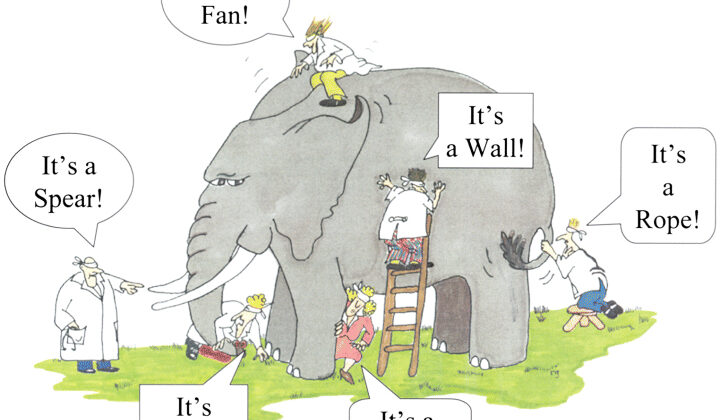

It seems everyone has a different perspective on the sources and types of problems we’re experiencing in IONM, and those perspectives depend largely on the individual’s work function. Interestingly, a business executive’s perspective may be very different from that of a clinician, but that’s only because they’re experiencing different parts of the same problems, which may be difficult to identify. It’s reminiscent of the parable of the blind men and the elephant.

If you’re not familiar with the parable, just image several people being blindfolded. They placed around an elephant that they can’t see, and asked to touch the unknown object in front of them and try to identify it. One person touches the tusk (spear), another touches the trunk (snake), another touches the leg (tree), and yet another touches the tail (rope). The point is, these folks only know what’s in front of them, and what they’ve experienced. They don’t know the experiences of others, they don’t know the full context. IONM is kind of the same. Executive leaders, neuromonitorists, nonphysician doctors, neurologists… they only know their own experiences, and may not see the full picture. But, they could if they only had a better understanding of what others are experiencing. That’s the whole point of this episode, and the ones that follow!

Now, that’s not to suggest that y’all are blind to the circumstances and challenges, but you may be unaware of what aspects of the problems other people are experiencing, and how that impacts their perceptions of working in IONM. Neuromonitorists may be unaware of the challenges faced by executive leaders, and vice versa. So, what I want to do is outline the challenges we face today from the perspectives of executive leaders, managers, neuromonitorists, nonphysician doctors, and neurologists. I think you’ll find there’s a common theme.

As I talk about the experiences of people in different positions, as someone working in that role, I’m sure you’ll agree with the perspectives, but I’d really like to ask you to pay particular attention to the perspectives of those working in the roles you’re NOT in. For example, if you’re a neuromonitorist, try to understand what neurologists and executive healthcare leaders are experiencing. I think you’ll find their different perspectives enlightening, because what they’re experiencing impacts you significantly… and vice versa!

What’s interesting about the various stakeholders whose perspectives I want to review is I’ve been in each of these positions. I’ve been an executive leader/CEO of a multi-million dollar IONM company, I’ve been a neuromonitorist, I’ve been a manager, and I’ve performed the professional aspects of IONM (including data interpretation and technical supervision) both remotely and onsite. I’ve also got years of experience as an expert witness in medical malpractice case involving IONM. I’ve lived everything I’m about to talk about, but I’ve also been connecting with people at all levels and hearing their stories, their challenges, and their concerns. THAT’s what I want to talk about today.

Let’s start with executive leaders of outsourced technical services companies. Collectively, these folks employ about 75% of all technologists, and are ultimately responsible for running the companies that cover the same percentage of cases across the country. The reason I’m starting here is because 1) they are on the front lines of the financial challenges we are seeing in IONM, and 2) so many people are impacted by the decisions they need to make in order to maintain the businesses that employ the majority of technologists, neurophysiologists, and neurologists.

In speaking to these folks, I hear very similar stories. They tell me they’re concerned because it’s more difficult to get reimbursed for services, so money is increasingly tight, and they need to run a lean business with slimmer margins. They worry because they have employees (and their families) who rely on them to maintain a profitable business that provides stable employment. Their Business Development teams are landing new accounts with facilities, but only as replacements for under-performing accounts that have been cut, or profitable accounts that have been lost to the competition. The business of IONM has become a zero-sum game – the only way to get new business is to take it from a competitor. Unfortunately, new business comes at a price because hospitals only care about cost. So, the winner of a contract is the organization who’s willing to do the same work at the lowest cost. Professional reimbursements used to make up the margin, but that’s changing because insurance companies aren’t paying like they used to.

The No Surprise Act has made things worse. Arbitration is expensive and the process slows down the revenue cycle, which means there’s less cash on hand to manage the business. Executive leaders are struggling with the fact that employees at all levels want to work less, make more money, and have more time off. Clinicians at all levels want to work three days per week and not take call. Everyone is talking about burnout! When it comes to technologists, it seems they’re always complaining about work hours, working conditions, and travel. Everyone wants the easy road to getting rich.

Inexperienced tech hires are graduating from neurodiagnostic programs with no experience and demanding six figure salaries. Executive leaders want to take care of their employees, but at what cost to the existence of the business? Technical services companies are losing front-line employees in record numbers as attrition rates have increased from 5% to 20% (or more), and replacements are difficult to find because employees are seeking jobs outside of IONM.

Leaders have made some difficult operational decisions like downsizing management, eliminating Education and QA programs, closing under-performing markets, and consolidating smaller markets into larger regions. Some have even cut employee salaries to maintain the business, which is difficult for employees who are experiencing inflation – which is a worldwide problem right now – making it more difficult for people to make ends meet. Owners of smaller companies are realizing they missed their opportunity to sell when times were good, and corporate valuations are dropping faster than reimbursement rates. Even seasoned executives are privately wondering how long the business can sustain the current climate.

Managers and Directors work in both the insourced (e.g., academic) and outsourced (i.e., private/contracted) settings, but pressures are the same everywhere. While some managers lead the few remaining programs in Quality and Education, many are tasked with coordinating teams of neuromonitorists to cover cases.

Managers tell me they’re faced with tighter budgets, fewer employees, larger geographic regions to manage (in the outsourced setting), and many are being tasked with jobs that other people used to do, like case coverage, new hire training, and basic HR functions. Worse yet, there’s increasing pressure to train inexperienced hires toward independence in a shorter amount of time. A decade ago, a new hire might spend a year in training before working independently. Today, training may last 2-4 weeks.

Managers deal with the consequences when they field complaints from surgeons, neurologists, and others who’ve seen a marked decline in quality over the last few years. Everyone worries about the next patient injury that could have been avoided with better trained staff. Malpractice concerns amongst managers aren’t as high as they should be.

Front of mind for managers is feeling high levels of stress because they get pressure from above and below. Many report feeling largely unsupported by leadership. Managers deal directly with employees that want to work less and not take call. They hire and train employees and do their best to support them while simultaneously trying to keep operations running smoothly. Despite best efforts, they losing employees faster than they can hire them, and executive leaders are blaming them.

Managers go on LinkedIn and see passive-aggressive posts like, “People don’t leave companies, they leave bad managers,” and they wonder if anyone understands they’re just doing what they’re told – often serving as leadership’s scapegoat. Historically, the biggest problem with IONM managers was their lack of management training. People were promoted to these positions due to tenure and/or clinical experience, then left to figure out the rest.

Today, most managers in IONM are struggling because they lack the training and resources necessary to lead in general, and now they’re being asked to do more work with fewer resources. Their bosses don’t support them, and their employees don’t appreciate them. They don’t know how long they can continue under the circumstances.

Neuromonitorists tell me they’re experiencing many of the same problems that have vexed them for years: long workdays with no food or bathroom breaks, rude hospital staff, uncooperative anesthesia teams, angry/dismissive surgeons, and having to wear those stupid red caps and paper scrubs while their clothes get stolen from the locker room.

Experienced neuromonitorists often report they are [and I quote] “tired of being bossed around by neurologists who”, in their words, [again I quote] “don’t know what it’s like in the OR” and “aren’t the ones getting yelled at by surgeons.” Again, don’t get pissed at me. These are their words, not mine, but the sentiment is out there, and it’s rather prevalent.

Inexperienced clinicians don’t understand what they’re doing wrong when they get criticized by physicians, probably because they’re largely under-trained. Under-training of neuromonitorists is problem that must be addressed in our field, and, I’m sorry to say, the CNIM isn’t the solution.

The tighter budgets, larger regions to cover, and downsized workforces are resulting in salary cuts, loss of bonus, reduced PTO, excess travel, and jumping between multiple rooms to cover back-to-back-to-back cases with aging IONM systems that are prone to dysfunction or break. The work is extremely stressful – far more so than leaders tend to appreciate – and they feel like no one understands or cares that 30 hours under high stress is the same 50 hours under little stress.

What’s wrong with wanting a more consistent and predictable schedule? What’s wrong with wanting to work closer to home? What’s wrong with having work-life balance? Many neuromonitorists want to get out of the OR, but middle management positions are filled, and others have disappeared, so there’s no opportunity for advancement.

Many neuromonitorists want to have more time for building a family and spending quality time with them. They worry about finding and affording reliable childcare at odd hours, paying down student loan and mortgage debt, and finding some consistency in their lives when work hours are long and unpredictable. Some even worry about falling asleep at the wheel after a 15-hour workday, which may be one of several in a week. Many neuromonitorists think the same job will come with better experiences in a different organization, but that’s rarely the case, so they’re starting to look for jobs outside of IONM.

Neurologists tell me they’re struggling with burnout, too. It’s reasonable to estimate there are approximately 600,000+ cases/year monitored in the USA, and probably 100 or so neurologists performing IONM full time. Declining reimbursements and a limited (some would argue declining) neurologist workforce make concurrent case coverage an absolute necessity. Concurrent case monitoring has been around as long as physician supervision, but it’s suddenly become fodder for malpractice attorneys who cite old guidelines representative of the academic IONM model.

The malpractice climate has become ugly in recent years, and neurologists are increasingly under the microscope. Learning from the collective conscience of the medical malpractice world, they’re having to do more work that would otherwise be unnecessary, such as typing more disclaimers into chat to protect themselves, much to the ire of neuromonitorists and surgeons.

Neurologists rely heavily on highly trained and competent neuromonitorists to collect high quality data and communicate with them so there’s a clear understanding as to what’s happening in surgery. Unfortunately, the budget cuts and employee turnover on the technical side have resulted in technical performance that, on the whole, appears to be incrementally worse over time. The data quality is worse, the communication is worse, and more technical handholding is needed. This adds layers of stress and complexity to remote physician supervision, particularly in the context of managing concurrent cases.

Neurologists often hold licenses in many states, and privileges at dozens or hundreds of facilities. Those without administrative resources need to self-manage those licenses, privileges, and all the CME requirements that go with each, not to mention scheduling and billing, all in addition to case coverage and associated charting.

On top of all that, most neurologists who work full time in IONM do so from a home office, often spending the entire day alone interpreting data and jumping between chats with neuromonitorists they barely know. Working alone for hours on end is more mentally taxing than most people understand. For neurologists working in the private sector, the money is great but it comes with high stress, most of which should be avoidable, and many wonder how long they can sustain this lifestyle.

I’ll carve out a separate section here for nonphysician doctors, the DABNMs specifically, because their experience has its nuances. Many of these folks transitioned out of clinical practice in the years following 2009 when IONM became the practice of medicine. There was an overall feeling of displacement and marginalization.

Rather than give up their professional careers and transition to working as a technologist, they worked their way into leadership positions as operators, educators, and quality directors. Over the last decade, they’ve played key roles in managing important aspects of clinical and corporate infrastructures. They tend to earn decent salaries but, unfortunately, recent budget cuts have resulted in some of these folks losing their jobs. Sure, they could have gone back into the OR, but the $100K pay cut and demotion to the level of technologist was too much to swallow. Some have left the field, while others provide consulting services.

What’s most unfortunate is the “brain drain.” We’ve lost some of the most talented and experienced neurophysiologists in the world who would otherwise be providing high quality patient care if only they were valued for the high level of expertise they bring to the table.

Recently, the ACNS, AANEM, ASNM and ASET released a guideline statement acknowledging that DABNMs – again, the nonphysician doctors who hold the DABNM, can provide professional-level interpretation and oversight (under general physician supervision), and this opens lots of doors for over-burdened neurologists and historically under-appreciated DABNMs. The DABNM working as a midlevel practitioner is a “practice model” that is ripe for expansion, but it’s unclear how this works in the context of current billing models and other regulatory hurdles. In the meantime, DABNMs are left with unappealing career decisions, and many wonder how long they can sustain working (or trying to work) in this profession.

What I’m hearing from everyone working in IONM is a lot of concern about the future. I think there’s general agreement that IONM isn’t going away, but everyone is asking themselves how long they can keep this up. At every level, people feel stress, burnout, confusion, anxiety, fear, and depression. So, perhaps it’s a good place to start by acknowledging that everyone is in the same boat. Individual experiences may differ (much like those of the blind men with the elephant), but everyone is feeling the same thing.

Think about that: everyone is feeling the stress. You are not alone.

Now that we’ve identified the fact that there’s an elephant in the room, I want to speak directly to the people working at these different levels of IONM. I’ve dedicated the next three episodes to a deeper dive into these topics by addressing issues that affect everyone working in IONM.

Please join me next time when I’ll be talking to and about executive leaders in the neuromonitoring space.

In the meantime, please feel free to leave a comment below, or send an email to [email protected]. I’d love to hear from you!

I’m Rich Vogel, and that was Stimulating Stuff!